Exploring Imposter Syndrome

Part I

An in depth article on imposter syndrome, how it affects us, and how to approach it.

“Nearly 80% of artists on Spotify have less than 50 monthly listeners,” this is an intimidating figure especially since there are over 11 million artists and creators on the Spotify platform, which means that there are millions of artists whose music isn’t even close to hitting the triple digits of listeners. With statistics such as these, it may sometimes feel like, as artists, what we’re doing is pointless, that we’re not good enough, that we’ll never “make it.”

With the current music market being what it is, it’s no surprise that imposter “syndrome” is such a big deal for individual artists and creators looking to expand their audience and make a living off of their music. However, creatives aren’t the only ones to experience this, people across a wide variety of fields have been demonstrated to feel the effects of this phenomenon.

What is imposter syndrome?

Succinctly put, those who struggle with imposter “syndrome” believe that they are undeserving of their achievement, despite any accomplishments they might acquire.

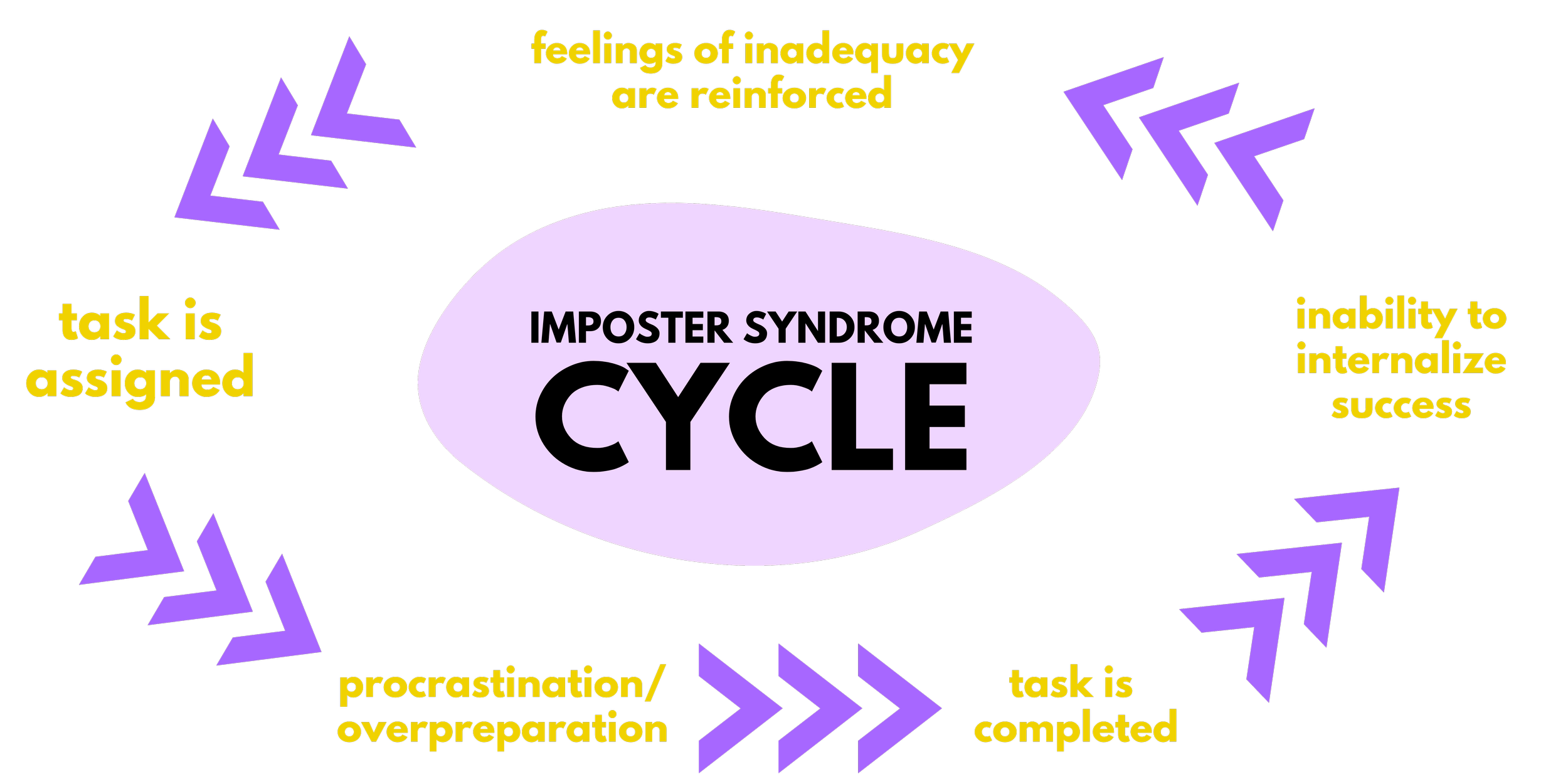

The imposter “syndrome” is often experienced in a cyclical fashion, in which the individuals suffering from it are assigned an achievement-based task, and once they accomplish the task, despite whatever positive feedback they may receive, they attribute their success to either hard work or good luck, but never to their own ability. Because these individuals aren’t able to internalize their own success, these beliefs reinforce themselves the next time they’re assigned another achievement-based task.

DISCOVERY

Initially, the imposter “syndrome” was thought to predominantly affect women. It was first explained in the 1970s, by Pauline Rose Clance, as the “imposter phenomenon.” Her study found that a large selection of high achieving women believed that they attained their success because they had been overestimated by their employers or had simply gotten lucky. The women included in the sample of their study were all extremely accomplished individuals, some of them even had multiple graduate degrees and several years of expertise working in a given field. In this study, which was aptly titled “Imposter Phenomenon in High Achieving Women,” they compared the results of women to men, who were found to be less likely to show symptoms of the imposter phenomenon. Nevertheless, today we know that the imposter phenomenon can affect a wide variety of people.

After Clance published her findings, many mental health professionals were inclined to believe that the individual’s psyche was predominantly responsible for feelings of inadequacy and the inability to internalize success. Many believed, and many still do, that imposter phenomenon was really a psychological condition, and those who have certain traits, such as perfectionism, or struggle with anxiety disorders are predisposed to the “syndrome.” Today we know that this isn’t necessarily the case.

A CONTEXTUAL APPROACH

The issue with an individualistic, psychological approach is that it doesn’t take into account the fact that a person’s environment is a huge factor when it comes to the imposter phenomenon. Recent findings have shown that people are more likely to feel like “imposters” within contexts that signal that they are so. In other words, humans do not live in an isolated vacuum: the world around us and the situations we’re in can influence the way that we feel. For this reason, many studies have found that women, gender minorities, and ethnic minorities are more likely to feel like “imposters” after accumulating success. For decades, professional and academic institutions and organizations were predominantly populated by white men, and, in these environments, a series of negative stereotypes concerning women, gender minorities, and people of color plagued several fields of work and study. If a person is working amongst a group of people that holds the subliminal (or even explicit) belief that their gender or ethnicity is less capable of achievement, that person is more likely to feel as though they don’t deserve the success they have acquired, that they got lucky. In other words, instead of trying to “fix” the individual, the goal should be to correct the environment.

Sources:

Clance, Pauline Rose, and Suzanne Ament Imes. “The Impostor Phenomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention.” Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, vol. 15, no. 3, 1978.

Feenstra, Sanne, et al. “Contextualizing the Impostor ‘Syndrome.’” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 11, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.575024.

“Imposter Syndrome.” Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/imposter-syndrome.

Ingham, Tim. “Nearly 80% of Artists on Spotify Have Fewer than 50 Monthly Listeners.” Music Business Worldwide, 25 Apr. 2022, https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/over-75-of-artists-on-spotify-have-fewer-than-50-monthly-listeners/.